Between terrible weather, fertiliser costs, and labour shortages; fresh produce is costing more these days. To be honest with you, I don’t pay too much attention to the cost of produce in supermarkets because we either grow most of what we eat, or buy locally. But every so often I catch a glimpse and increasingly, I’m very happy that particular thing is growing in the garden.

When it comes to home gardening, some vegetables are more ‘profitable’ than others. After considering the time, effort, and opportunity cost, there are a range of veges and herbs that will have a healthy return on your initial investment, while others might cost you more to grow than to simply buy.

We don’t bother with the effort to grow mushrooms, onions, or sweetcorn. For various reasons, they all make more sense to pay for. We also buy frozen peas and canned tomatoes (because growing and processing is not worth the effort compared to cost), but other than that, we are fairly self-sufficient in the things we eat from our garden. I’m a bit cheap by nature, so over the years I’ve honed our system to be fairly cost-effective.

With prices on the rise and a potential recession looming, if you are lucky enough to have a garden, there’s a good chance you’re using it. I don’t think taking up gardening is a way to solve the issue – a garden is an expensive and time-consuming thing to set up from scratch.

But assuming you already have the space, equipment, and motivation to dig some soil; being selective about what you use that space and time for can impact how much money your gardening effort actually saves you in the end.

Potatoes

Hands-down the most fun thing to grow, and the maths works out. They’re pretty easy to store, so they can be grown in bulk to feed the family over winter. They take 2-3 months, which is pretty fast. And you can grow them in containers or bags if you don’t have an actual garden.

It’s taken years to get it right, but we need 4-6kg of seed potatoes to grow enough to feed the two of us throughout the year. The cost of those can vary wildly. At a box store, they’re around $10/kg. However I’ve found a local garden center that allows customers to buy ‘free flow’ seed potatoes from giant sacks for $4.95/kg – halving the initial investment. It pays to shop around.

So in our household we’re looking at a $30 investment for a full-year’s supply of potatoes – which for us are our staple carbohydrate. We could reduce that further by using our own potatoes as seed the next year, however so far I’ve opted to keep using certified seed.

Agria potatoes (which are comparable in quality to what we eat) retail at around $4/kg, meaning we need to harvest at least 7.5kg to be economically viable – and we are usually pulling up more like 20 kg.

We grow two rounds of potatoes – 1-2kg of ‘earlies’ (usually Jersey Bennes) are planted in late winter (though in colder regions I’d recommend waiting longer, as a frost will kill them). Then in October, we plant out 3-4 kilos of our main crop.

The fresh baby spuds are mostly an annual spring treat. They’re worth planting even if you’re not aiming to become entirely self-sufficient in potatoes just because baby spuds straight out of the soil are so good.

For us, they fill a gap between the main season crops. We frequently run out of our stored spuds just a little before the next round is ready for harvest, these keep us going and change things up a bit.

Our main crop is a mix of Agria and Desiree. Last year the Agrias produced 500 gram monsters the size of adult shoes; while the Desiree proved just as good to eat, but significantly more prolific, meaning a higher yield per plant. They’re ready to harvest in January. We’re eating the end of last year’s crop now.

Now’s the perfect time to plant main both early and main crop spuds right across the country. Here’s how to choose and plant your potatoes; and here’s how to harvest and store your potatoes.

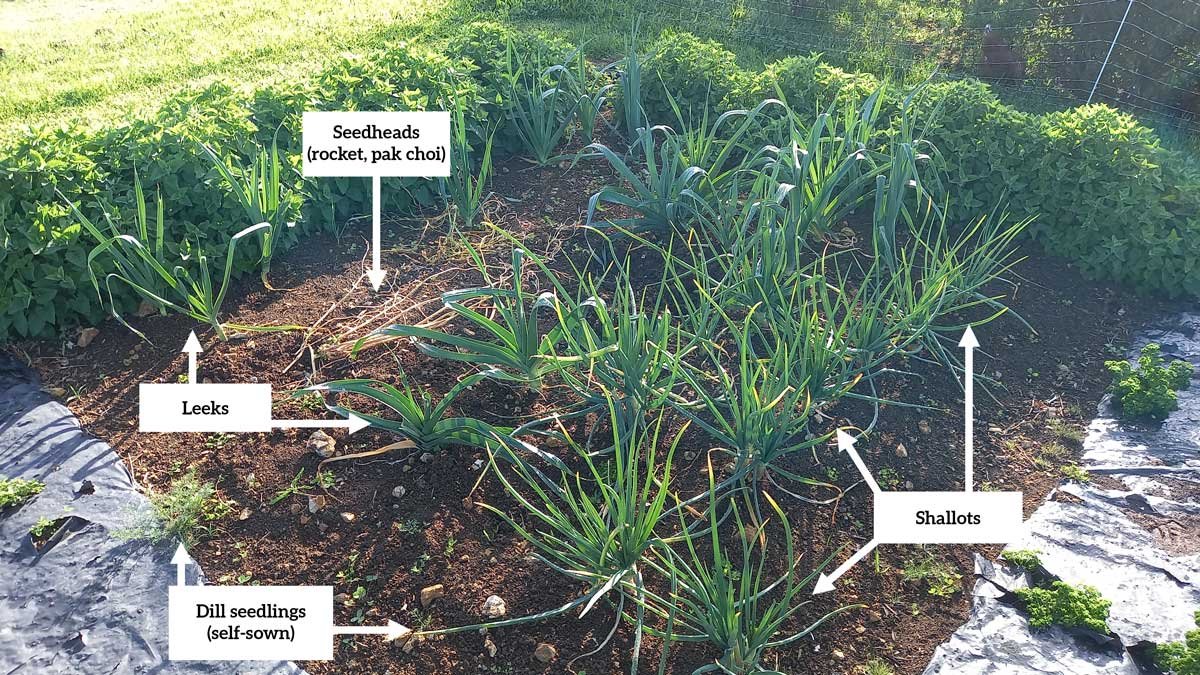

Leeks

I’m really surprised leeks have made this list. I grow them because I like them, but they take forever. Leeks are going to tie up your vegetable bed for more than 6 months, and probably closer to a year once you actually eat them.

There’s a big opportunity-cost to them. You could grow many other things in that space over that time. In a small garden, it might be worth just buying them, especially in peak seasons when they’re usually fairly cheap.

But recently my supermarket was selling leeks for $3.29 each in season, while a packet of seed costs $3.18 at my local hardware store. When a packet of 300 seeds is 11 cents cheaper than a single leek, the maths is beginning to work out if you can afford the space and time.

Last year I purchased seed and sowed the entire packet. I then gave half the seedlings to a neighbour who also enjoys leeks. We’ve both been eating them all winter. Two households fed for $3.18. It worked so well we’re doing it again this year.

The trick to leeks is timing – sow your seeds between now and the end of November. Then plant your seedlings between late January and the end of February. There’s a couple of tricks to planting them, but I’ve got you covered.

Once they’re in the ground, you mostly get to forget about them until they’re ready to eat in May-June. Keep the weeds down, but if you’ve sown and planted at the right time, they’re pretty easy.

Self-seeders

In my garden, I don’t plant lettuce, rocket, coriander, dill, parsley, or pak choi; they plant themselves. I call it lazy gardening.

I let at least one (and usually several) plants go to seed each season. Beneficial insects and bees love the flowers, and the seeds equal free plants for us.

Once the seed-heads are dry, I spread them around the garden in places I wouldn’t mind them growing in the future. But that’s about all the work I do.

I purchased one packet of ‘Michelle’ lettuce in 2017. We decided we liked it, and when we moved, I bought along seeds I had collected from the lettuces I grew. We are still growing the decedents of that single packet of seed.

So when lettuces hit $8 each in stores, my garden is literally growing them like weeds. None of these things are particularly cheap to buy (and frequently come with a lot of plastic packaging), but they are entirely capable of just growing themselves. I can usually find them somewhere in my garden when I want them.

With herbs like dill or coriander, the seeds are also a spice. We collect them and refill our own supplies. It doesn’t save a whole lot of money, but it’s a nice added bonus to have home-grown fresh spices.

Don’t bother trying this with ‘F1’ varieties, and lean towards heritage seeds. You want something that will reliably produce the same thing each year. As a shortcut, anything that Kōanga Institute, or Setha’s Seeds sell will work. Once you settle on what you like, just don’t pull it out when it starts to bolt.

The biggest learning curve is in seedling identification. If you know what you’re weeding, then you’ll have some say in where they grow. But just letting nature do it’s thing is probably my biggest tip for saving buttloads of both time and money in the garden.

Courgette

If you’ve ever grown courgettes, then you understand why they’re on this list. They’re almost fool proof, and often prolific.

You don’t need many courgette plants at once. In general, I’d suggest planting two seedlings in October and January. This will give your garden a constant supply from December to April.

Seedlings are increasingly priced at around $5 each and can add up when purchased individually. But they grow pretty easily from seed. In which case, sow four seeds in September and December, planting out a month later. I find it pays to scatter them around the garden. Just fit them into any gap you have at the time.

The biggest issue I always have with them is mildew. That’s why spreading out the timing and spacing of them works – each plant produces, then dies; while you retain a regular supply. Mulch them well and water with drip irrigation if you can. This will avoid getting excess water on the leaves, decreasing the chances of powdery or downy mildew.

Keep an eye on them and harvest while they’re small. They can be pickled or frozen to store – try grating and freezing them in muffin tins so you can throw them into winter meals. They also make a pretty great cake.

Shallots

Honestly, probably the easiest member of the allium family to grow. We plant 6-10 of them each winter, and at Christmas we harvest more than a year’s supply for us.

They dry easily and store fantastically. My initial investment in a couple bags of Henry’s Flowering Shallots from Kōanga in 2019 has paid off several times already. I’ve sent a few sets off to friends and family over the years to start their own as well.

Shallots can replace onions in most recipes. They take about 6 months to grow, but they take up hardly any room and are super low maintenance. Just cool little dudes doing their thing, needing absolutely no attention until they’re ready to be harvested.

Conversely, if you prefer shallots to onions, then growing them will save you a tonne of money. My local supermarket is selling them for $15.20 per kilo right now. You can harvest that off three planted shallots, easy. Maybe even two.

Anyway, for a second here, let’s go back to that image at the top of the post and look at it again to see how this looks when it’s all working together:

A note on my privilege

I don’t believe individual vegetable gardens are the answer to poverty. And I know it takes a whole bag of privilege to be able to grow things. Especially when you’re getting started, gardening is not a cheap way to spend your (possibly limited by other factors) time.

Both sides of my family have a strong, multi-generational tradition of vegetable gardening; and I grew up with a backyard containing a vegetable garden bigger than some flats I have rented. Harvesting my dinner from a big vege garden is my ‘normal’, and working in the garden is my idea of ‘fun’; but it’s not everyone’s.

I also have security of tenancy. That’s not something I’ve had the privilege of for my entire life, and I know how being a renter limits your options. There’s a really big gap in my gardening experience timeline and it can be summed up by the words “insecure housing”.

If I put something in the ground, I know I’ll be able to harvest it in the coming weeks, months, and years. But if you are subject to insecure housing, then the investment in gardening doesn’t make any sense at all. I understand that.

So before I sign off, I do want to acknowledge that gardening doesn’t help much when you’re time and cash poor. A pack of seeds will not outrank a loaf of bread in terms of priorities when you’re hungry.

I am in no way suggesting that gardening is the answer to inequity. Rather I’m encouraging those of us who can and do garden to think about it a little smarter.

As a small way to address the balance, we regularly take our excess produce and eggs down to our local community food pantry. If you share my privilege of a productive garden, then I’d encourage you to find a local food pantry or pātaka kai too.

When you’re facing a glut and supermarket prices are soaring, it’s one small way to give back. Just don’t be the dick who dumps a bunch of marrows at the pātaka kai (there’s always one). Maybe find someone with chickens and swap them for some eggs instead.