As someone who is both concerned by climate change and owns cows, agricultural emissions are a topic that interest me. How should I be held accountable for the methane my cows burp and fart daily into the atmosphere?

I do believe there should be a mechanism to pay for the methane and long-lived gasses livestock farming produces. They are a cost of business.

If the planet is carrying that balance, then we’re only deferring those debts for future generations to pay for instead. This country has already deferred around 150 years of pollution; how much longer can that continue?

We are very small farmers. While the amount of land we have is rather large compared to a suburban section, it’s small compared to a dairy farm, and we purposely understock it.

But it turns out the proposals currently on the table won’t affect us anyway. Even though they fart and burp like every other cow, we don’t have enough livestock to qualify.

Our numbers

We have 15.581 ha of land. That’s 38.5 acres, or 38-and-a-half international rugby fields.

Of that, 8.75 ha is ‘grazable land’ – grass (and gorse). I happen to disagree with what constitutes ‘grazable’, so we actually graze 7.47 ha. There is one paddock that is basically permanently fallow until we can plant it back into natives, or it does it by itself.

4.419 ha is in a separate title. It’s entirely pre-1990 native forest, fenced and protected by council covenants. On the main title, there’s an additional 1.22 ha of fenced and protected pre-1990 native forest, and 0.715 ha of fenced-off area being allowed to regenerate under gorse. The balance is non-grazed areas such as living zones, races, driveways, gardens etc.

We have 6 cows. They are glorified lawnmowers and we’re now on our third herd. We bring them in somewhere between 6 months and 1 year of age; then send them off again around 2 to 2-and-a-half years old. In farmer terms, they are between 4 and 5 ‘stock units’ each. So we tend to carry a maximum of 30 stock units.

As they get bigger, the cattle cause more erosion and pugging, so there is a limit to their time here. The topography of our paddocks is pretty steep and big cows running around can cause some real damage to the soil.

We also plant native trees – 100 our first year, about 50 in year two, and about 350 this year. We focus on eco-sourcing seeds from our existing bush and raising our own trees to keep costs down. I refuse to plant pine, though some other non-natives planted for continuous-canopy harvesting in the future is a possibility.

We do not apply synthetic fertilisers to our grass or crops. The grass just grows, and the gardens get things like cow manure, compost, and worm castings.

Our choices

We are not reliant on the income from our cattle, but it does allow us to do things like pay the rates and make repairs to the driveway. It’s not insignificant to us, but it’s also not our main income source.

It’s an important distinction between us and a farmer who is reliant on livestock for income. It means we have more flexibility in our choices. We have made the choice not to extract every last cent that we can from our land.

We could choose to graze every available inch of pasture. The cattle could stay on farm for longer, so they’re bigger when we sell them. Or we could run more cows so we have more to sell.

With a bit of fencing work and environmental ‘compromise’, we could keep another 4 cows here. We could probably double the herd if we applied synthetic fertilisers to improve grass growth and went harder on the gorse. But we don’t do any of that.

The one situation we never want to face is too many mouths and not enough food. Our first summer here was very dry. With 4 cows at the time we got through it fine, however we saw the effects on other properties and on the stock price.

We’ve seen a quite-bad year. We don’t want to get caught out in a really bad year because we got a bit greedy. I don’t have much of an appetite for risk and I’d rather take the safe route than the gamble.

The long-term goal

Not that any of that ideology or thinking matters. The current round of legislation is aimed at farmers with almost 20 times the number of livestock we have.

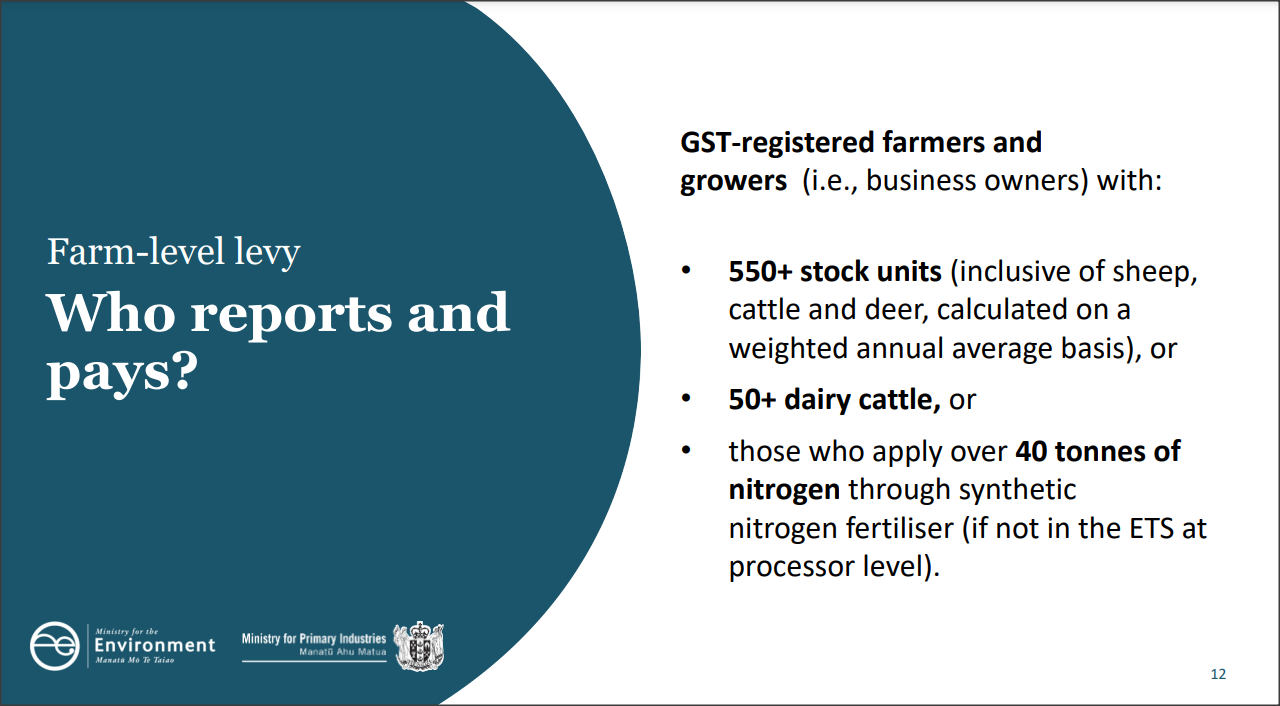

It doesn’t affect us at all as it stands. The reasoning is that it would be far too complex to bring in smaller producers by 2025.

Lifestyle blocks make up about 5% of New Zealand farmland (PDF). Most of us keep some kind of livestock – everything from alpacas, to pigs, horses, cows, sheep, llamas, deer, goats, pheasants, chickens, geese, ducks and more. Most of us won’t even come close to the 550 stock unit (I am at 30, remember) criteria.

Collectively, that’s a lot of farts that won’t be measured under the proposed scheme. But I can also understand why the government is choosing to make the biggest gains first.

Personally, I think we will be asked to account for our emissions once things have been ironed out with the ‘big boys’. Eventually, our 5% stake of the market will become the ‘low hanging fruit’ to keep bringing emissions down.

This proposal and following legislative changes are worth paying attention to because even if it doesn’t affect us now, that would be an easy thing to change once the system is up and running. Agriculture makes up 50% of our country’s emissions, and lifestyle blocks are collectively 5% of that figure.

Gross greenhouse gas emissions in 2020 via Ministry for the Environment.

The current goal for 2050 is aiming for a 24-47% reduction below 2017 in biogenic methane emissions and net-zero emissions for long-lived gasses. Somewhere between now and then, I think they’ll bring us into the scheme as well.

Big gains will be made pretty early on by targeting big herds. But that will slow down as farmers adapt and settle into the new scheme. As it does, adding in another 5% of potential emissions in the form of lifestyle-block owners to keep making gains will be an obvious step.

The proposal

The problem with the current proposal is it lacks some very important certainties that matter a lot when forming an opinion.

Under the proposal, prices will be set by government Ministers on the advice of the Climate Commission. This is a sticking point, and a bit of a scary thought when you consider the political spectrum ranges from ‘scrap this whole thing‘ to ‘this does not go far enough‘.

It’s also unclear how much or what kinds of plantings and technologies will be recognised for credits under the proposal. These are things that are still being ‘worked through’ and will doubtless be refined as this proposal moves through the regulatory process.

The proposal signals future changes to the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), which could be of huge benefit to us. But it also discusses ‘multi-year interim contracts and grants’ with farmers for the purposes of offsetting costs, so I don’t think the ETS changes should be expected any time soon.

We’re still a few rounds of consultation away from the certainties that actually matter at the farm level, and the clock is ticking.

Heads in the mud

The Government has signaled that this will happen by 2025. It is asking farmers to come to a consensus on how that might be achieved. All of us get to have our say, whether you own livestock or not.

But if the industry spends this time quibbling about it and running it through endless rounds of consultation, then the Government will simply implement a processor levy. This will mean that milk and meat producers, as well as fertiliser manufacturers and importers will simply have a flat levy charged against outputs.

It doesn’t look like this option will take into account any planting or other mitigation measures. It will likely capture smaller producers that otherwise wouldn’t qualify under the proposal as well.

Something is going to happen, and pretty soon. We’re closer to 2025 than we are to say, March 2020.

It’s probably best we just try to keep up with it all and submit our feedback when it’s called for, rather than throwing tantrums by driving tractors down motorways.

Meeting goals

Others before us have run a much higher stock count. Simply by keeping our head count at 6, we have probably reduced the bovine emissions of this piece of land by around 40% from 2017 levels.

On an individual farm basis, we’ve probably already met the government’s 2050 goals through destocking. It doesn’t really matter if we’re financially rewarded or punished for it.

Our herd keeps the grass down enough that it’s not a massive pain. That’s it. That’s the goal here. They mow our very large lawn.

We have to turn them around every couple of years to stop them ruining our soils, and we make a bit of money off that. If we made a bit less money because we were paying for their wider environmental impact? OK.

I’m totally down with this path to the future. It entirely aligns with my personal goals (which themselves are fueled by my need to personally ‘do something’ about climate change and environmental degradation).

Each year we choose to take away a little bit more grass as we plant and then maintain our trees. If we keep making these choices, by 2050 I would like to say that of the 8.75 ha of ‘grazable’ land we had in 2019; at least 6 ha is now native canopy tree cover registered on the ETS. In theory, swapping our livestock income for carbon credit income.

That’s my goal anyway – to retire this marginal land and cover it in a cloak of native and edible forest. But in the meantime, our cows will be farting, and I will be planting.

Links and references

Want to do your own research or submit feedback on the scheme? Here are some helpful links:

Pricing Agricultural Emissions consultation survey (Ministry for the Environment) – when you’re ready, this is where you submit your feedback. There are 15 questions though you do not need to answer them all. Consultation closes 18 November 2022.

Agriculture Emissions Pricing Consultation: Public Webinar 1 – webinar hosted by the Ministry for the Environment to explain the scheme and answer questions.

Webinar slides (PDF) – source for most of the images used in this post.

Sign up for future webinars or Q+A sessions

Pricing agricultural emissions – A snapshot of the consultation (PDF) – simple overview of the Government’s proposal.

Can NZ really meet its methane emission targets? A reminder of what methane does, and why we need to reign it in.

Farm emissions scheme: Federated Farmers condemns Government’s agricultural emissions pricing plan – despite the click-baity title, quite a good overview of differing opinions and issues with the proposal from all sides.

We’re still bargaining when we should already be accepting – Bernard Hickey looks into the problem with more graphs and sources than I did.