Years ago, I watched with horror as a wasp carried a plump young monarch butterfly caterpillar off the swan plants I had so lovingly tended. It didn’t happen once – it happened dozens of times.

Every time my caterpillars started getting a bit bigger, a wasp would come and carry them off! I’m not alone. Seeing a wasp just pick up and fly away with a ‘good’ caterpillar is often what motivates people to deal with their wasp problems.

They turn to Google. They buy or make traps that never work. And their monarch caterpillars keep getting taken to feed paper wasp colonies.

Over the last few years, I’ve had to learn a bit about wasps in my role as a gardener. One of the biggest workplace hazards in my job over the summer months is stings from paper wasps.

I do my best to minimise the hazard, but I usually get 3 or 4 stings every year. No matter how careful I am, or how many cans of wasp spray the maintenance team goes through, I’m bound to blunder into a nest at some point.

Thankfully, I’m not allergic to paper wasps. A sting hurts, but it doesn’t hit me in the same way a bee sting does.

But because it’s such a concern for me, I’ve been pretty motivated to learn as much as I can about this pest over the last few years.

I’ve observed a lot – and so have my colleagues. I’ve talked to other people about their observations too. And I’ve noticed patterns of behaviour that can help you keep numbers under control.

More than one wasp

The first thing to know, is there is more than one type of introduced wasp in New Zealand. And which wasp you have makes a difference to what their impact is, and how to control them.

Vespula wasps (New Zealand is home to two, German (Vespula germanica) and Common (Vespula vulgaris)) are more aggressive, but easier to control. They’re the ones that will sting you multiple times if you blunder into a nest.

The Vespex sting

Vespula wasp numbers exploded at our place in 2025, so it was time to run a poison operation with Vespex.

The poison Vespex can be used to Vespula minimise populations, even if you don’t know where the hives are.

They are also the wasps the traps you’re making or buying are designed to capture.

Clockwise from top left: Vespula germanica (CC BY-SA 2.5 – Richard Bartz, Munich aka Makro Freak), Vespula vulgaris (CC BY 2.0 – Martin Cooper), Polistes humilis (CC BY 2.0 – Jean and Fred Hort), Polistes chinensis (CC BY 2.0 – Sid Mosdell).

But paper wasps (again, we have two, Australian (Polistes humilis), and Asian (Polistes chinensis)), don’t take the bait. Vespex won’t work on them. Neither will your average wasp trap.

And paper wasps (Polistes) are the ones taking your caterpillars. They prefer their protein wiggling. It’s exactly the reason Vespex doesn’t work, and neither will your traps.

Vespula wasps are happy to eat dead protein. Polistes aren’t.

Identifying a paper wasp

The easiest way to identify a paper wasp is by their long dangly rear legs.

If you’re watching the wasps, you’ll spot these hanging legs pretty easily, especially when they’re in flight. Vespula wasps don’t have the same ‘dangle’.

The only way I could get a decent photo showing that dangle was to use a dead one.

The difference between an Asian and an Australian paper wasp is a bit harder to pick. The Asian paper wasp is the classic black-and-yellow striped colouring, with orangey legs.

The Australian paper wasp is darker – leaning closer to brown than yellow. The legs are redder. I’ve found Australian paper wasps to be a little less aggressive than their Asian cousins, for what it’s worth.

In defense of the Polistes wasp

Paper wasps do fill an ecological niche. Yes, they eat monarch, and other native caterpillars. But they’re also helping to control your white butterfly, armyworm, and other pest insect populations.

When you look closer, you might also find them flying off with an aphid. They control pest invertebrate populations as much as they threaten the native ones.

They’re also pollinators as part of their diet comes from flower nectar.

Anecdotally, I’ve only been stung by a paper wasp when I was directly threatening their nest. They usually give a warning – a single sting, rather than a mob that follows you.

If you back off at that warning, they’ll probably leave you alone. Finding the nest is usually a matter of looking more closely at your immediate surroundings. Assuming you’re a person who isn’t allergic to their stings, then it’s more irritating than debilitating.

So on the scale of ‘good’ to ‘absolutely terrible’, paper wasps are somewhere in the middle. They have some benefits in the garden, and they’re not super threatening – unless provoked.

But there’s no doubt our carefully cared-for populations of monarchs certainly make easy pickings. And that it’s infuriating to watch them be carried off. It pays to keep populations low, especially in populated areas.

Prevention is key

As I write this, there is no cure. No baits or traps you can set. Because Polistes wasps have such a preference for live food, they won’t take a bait.

Prevention is your only option.

For your caterpillars specifically, you can net your swan plants with a bug or mosquito net. Or build a butterfly house.

Keep at least one plant outside the net to allow eggs to be laid, and transfer them one they’ve hatched. Release your butterflies once they’ve completed pupation.

But the other side of the coin is wasp control. In an ideal world, you’ll start keeping your eyes out for nests from early October.

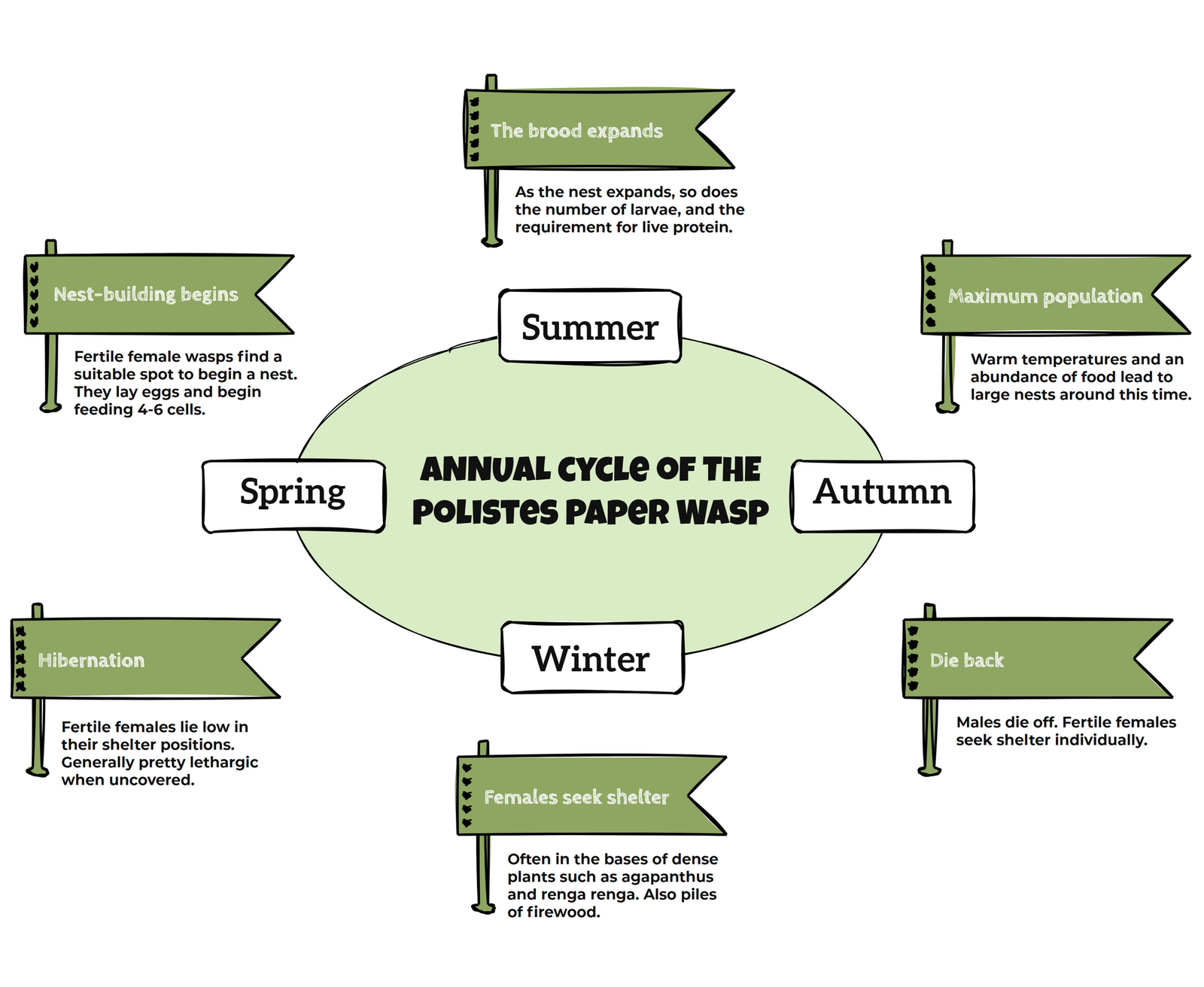

Fertile females find somewhere warm and calm to hibernate over winter. But as it begins to warm up, they begin their new colonies.

They begin to build a nest from timber particles, lay eggs, and seeking food for their new brood.

This Asian paper wasp started building her nest at the door to my garden shed earlier this month.

Controlling these nests while they’re small means they don’t build up numbers.

Walk around your property and find the wasp nests early in the season, and there will be fewer wasps taking your caterpillars later in the season.

Finding paper wasp nests

If you see a paper wasp flying by, there’s a good chance there’s a nest nearby. They don’t tend to go very far, and the nest is probably within 50 meters of where it’s flying.

Some common places we have noticed they tend to favour:

- Exposed, unpainted wood including fences and buildings.

- Metal containers and sheds.

- Under eves.

- On your roof, especially where two downward angles meet.

- Under solar panels.

- Inside bushy plants e.g. flaxes, ladder ferns, aloe, canna, hedging.

- On the outer branches of larger trees.

You’re looking for a roundish grey ball, hanging by a small arm. These nests can range in size from 10mm to 150mm, but are typically 40-60mm.

They can get pretty impressive (and frightening) later in the season.

Left: Asian paper wasp nest in a pittosporum. Right: Australian paper wasp nest in a yukka. (Click to expand).

Below: The largest paper wasp nest that I’ve ever encountered – it was less than 10 metres from our front door!

As the nests get bigger, you might spot a group of wasps hovering around it on a sunny day.

If you see three or four wasps hovering in one place, there’s probably a nest hiding within a metre of them.

Daily routine

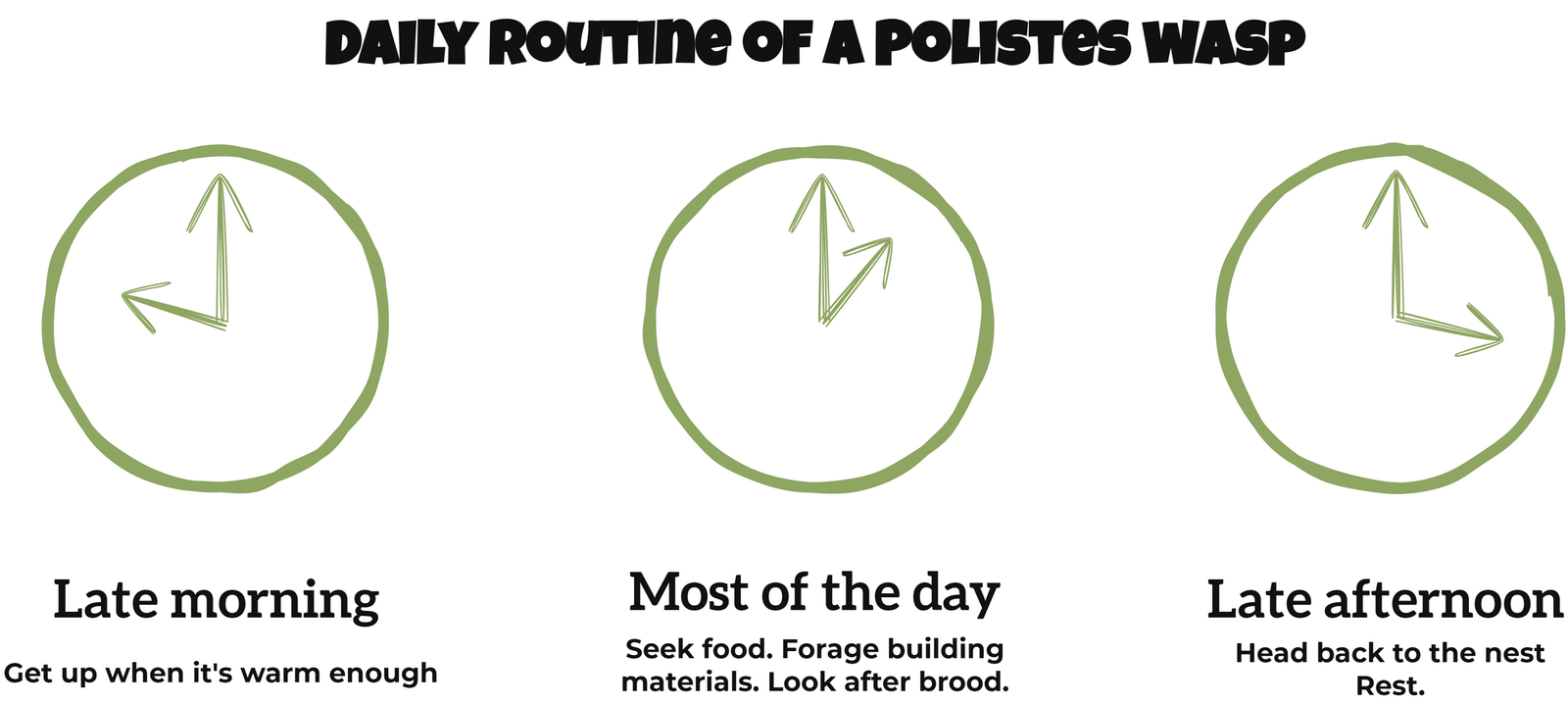

From spring to autumn, the the daily routine of a Polistes wasp is fairly predictable.

In my job, I tend to work from sunrise to about mid-morning. The risk of wasp stings increases the later I work, so I try to work in the cool of the morning at least in-part for this reason.

Paper wasps like a lazy lay-in until the sun gets warm at about 10am – sometimes earlier if they’re in a spot that gets early sun.

Then they spend the day foraging and bringing back food and building materials for the nest.

Before the sun begins setting, they head back to the nest for an early night.

Knowing this helps you find and destroy them.

The best time for finding nests is during the day while they’re active and flying about. Just watch. Look for groups hovering, or attempt to follow them. Sometimes flicking them with some flour helps you keep track.

The best time for destroying the nests that you find is either early in the morning, or towards sunset when everyone is home.

Nuke them

If your goal is to reduce your wasp population, the nest will need spraying. While there are specialist wasp sprays on the market, a can of regular fly spray will also do the job, especially early in the season while nests are small and only have a few occupants.

Later in the season, a specialist wasp spray might be worth having on hand. This is because the nests are typically larger and therefore present more danger.

A specialist wasp spray is able to project the chemical further – usually at least 4 meters. That means you can stand further back away from the hazard.

They can also contain a chemical that immediately immobilises the wasp on contact. So they’re safer, but they are 2-3 times the price of regular fly spray.

Fly spray means you have to get closer, but a good 3-4 second dousing will have a similar affect to the specialised sprays.

I am yet to have an angry wasp come after me once it’s been hit with a good spray of Raid or Black Flag. I do tend to spray early in the morning while they’re still dozy though.

Buzzed or bothered?

If you don’t live in New Zealand, then different advice will almost certainly apply. If wasps are part of your natural ecosystem, then they belong there, and learning to live alongside them might be the better position.

But here, Polistes wasps are introduced. Our (often threatened) native invertebrate populations have not evolved alongside either Vespula or Polistes wasp species.

It’s true that we can tolerate them to some extent. But it’s also true that to people who are allergic to them, these pests are life-threatening. They also impact our built environment as they collect material for their nests. In many cases, some level of control is necessary.

I hope my observations and explanations go some way to helping you with that.

Late in my research for this post, I came across this excellent New Zealand Geographic article from June 1995 – Paper Wasps – Guests or Pests? by John Walsby. It covers a lot of information I didn’t get to. Highly recommended if you found this post interesting.

If you wish to learn more about Vespula wasp species in a New Zealand context, then I equally-as-highly recommend The Vulgar Wasp: The Story of a Ruthless Invader and Ingenious Predator by Phil Lester. It’s probably in your local library.