A lot of Kiwis really associate themselves with the ocean. We’re an island nation, so of course that makes a lot of sense. But I have never really felt that way.

You’re unlikely to find me at the beach on a hot day. To me, going to the beach means sand everywhere, sunburn, body insecurity, constant thirst, and waves stopping my every attempt to have a swim. Instead, I like to retreat to the trees.

Our previous house lacked access to a good bush walk, or anything really resembling tree cover. The nearest public walk of any note was 30 minutes drive away.

In the heat of the summer (when the beach was actually really close), I felt like I was trapped in the middle of a grass desert. I’d ache for tall green trees.

Here at The Outpost, things are quite different. We have over 5ha of private native forest spread over 3 areas, and we bloody love it. When it gets hot in the afternoon we cover ourselves in bug spray, pack some water and retreat to the bush.

In spending more time in our ngahere, I’ve been confronted with how many different plants grow there. I want to treasure and look after this taonga, so I’ve been getting to know it better.

For most of my life, when I looked at a forest, I saw trees. Probably ferns. Maybe some moss. My ‘plant literacy’ was pretty low. Embarrassingly low given how much my Dad knows to be honest.

I saw the general picture, but I’d never really concentrated on the details.

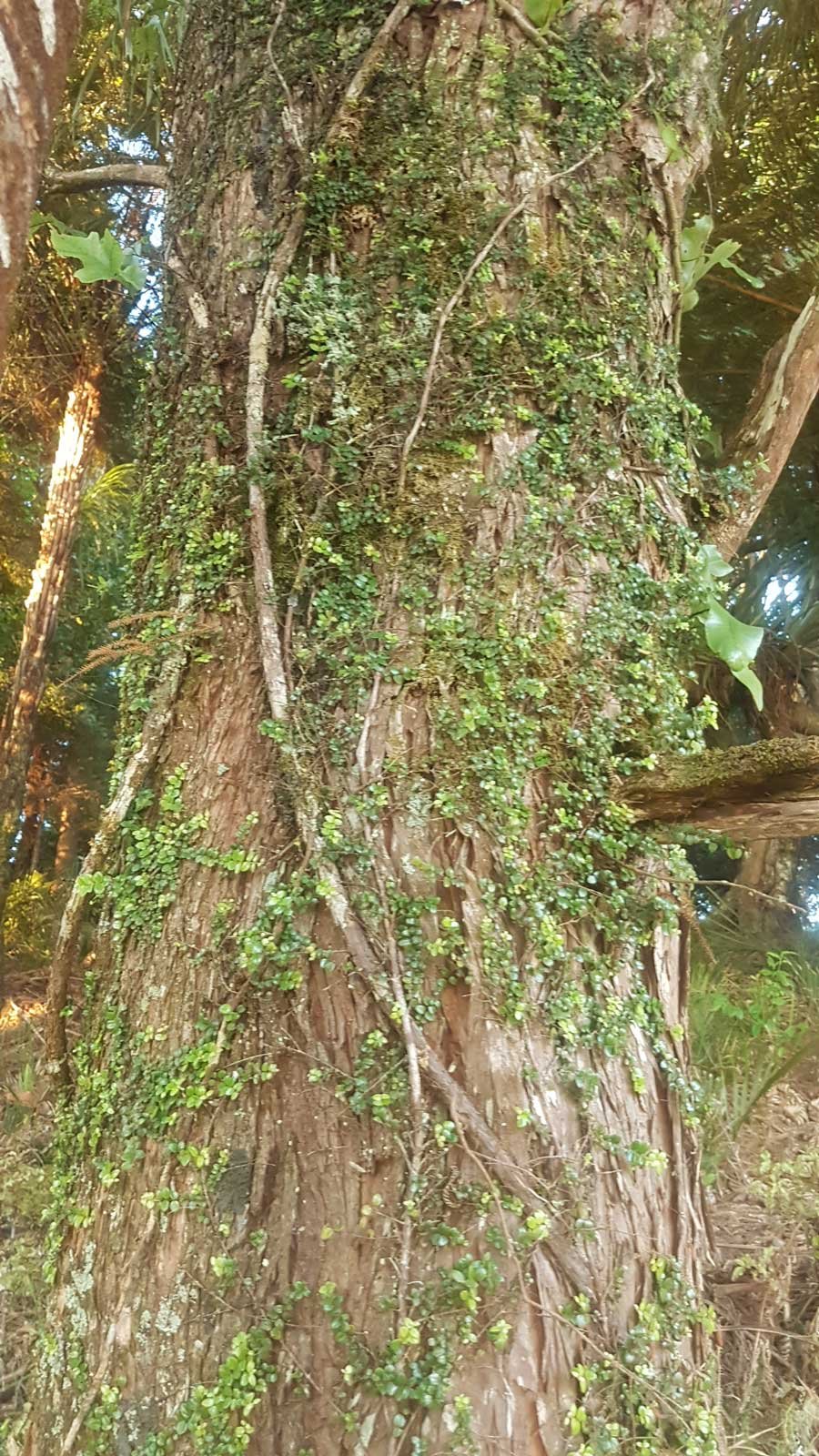

Sure, I could recognise a nikau, but it’s only been relatively recently I could tell the difference between mānuka and kānuka. And I’d never even heard of white rātā – which might as well be invasive it’s so prevalent here.

There’s at least two different varieties of ponga in our bush, and dozens of different ferns. There’s rimu, tairaire, puriri, patē, kawakawa, mingimingi, tōwai, native grasses, coprosmas… I’ve only just begun looking closely enough.

Walking through the bush now, I greet trees by their Māori name to practice. Sometimes even their latin name if I can remember it.

I’m getting better at identifying the ones that reach so far into the sky you can no longer see them too. I look at the leaf litter and seeds on the forest floor, and their bark.

Getting to know the forest means I’m learning which groupings like to live together. Some areas have a lot of tairaire, tōtara, and puriri. In other places, the kānuka and tōwai form most of the canopy. And there are incredible nikau groves smothered in white rātā and kahakaha which are easily 100-200 years old.

Learning the names of all the plants in the forest is going to take a while. I’m using iNaturalist to help me record, learn, and identify the wonders we find. As well as learning about our native plants, I’m also learning a lot about weeds – but I can write about them another day.

I really love having such easy access to the bush now. It’s an absolute honour to be kaitiaki to such an ancient and important ecosystem. This summer, one of my big projects will be completing a Bush Vitality Assessment on our big (4.5ha) block. This will form the basis of our pest and weed management strategies, as well as our replanting efforts.

I came here knowing a little bit. I grew up learning some things. I studied native plants formally and participated in a weekend rongoā class. But being here with my new eye for a plant’s detail is opening up an entirely new world. I can’t wait to see what other amazing gems I’m going to discover over time.